Joseph was a very high officer in Egypt, reporting to Pharaoh Thutmoses IV.

Status is very important in such a position, as is one’s family background.

It was in Joseph’s interests to show that his family had status in their own land.

So here is “Joseph’s official history” of his own family, in its context.

Joseph had his account written down in hieroglyphics and in Akkadian.

The tablets, in Akkadian, containing this account were preserved in Jerusalem.

They were recovered in the time of King Josiah, along with other tablets.

This story then became a vital part of the expanded story of Israelite history.

This account can be extracted from the book of Genesis.

It is a two-step approach. The first step is to find the very late “Priestly Source.”

This is easy, and well established by scholarship, tested over 100 years.

Next, anachronistic elements can be removed and things reconstructed.

It is a wonderful story, but it is not a “family story:” it is an official story.

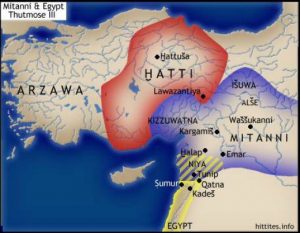

It is given here, with its undisputed historical context, which is shown in red.

To this I have added the results of my own historical analysis (in green).

So here is Joseph’s story, taken from the Bible, re-written in the first person.

My great-grandfather was Abram, our ancestor.

He came from Haran, otherwise known as Ur of the Chaldeans.

He took with him Sarai, his wife, Lot, his brother’s son, and all their goods

And set out on an adventure, to Djahi, together with all their servants.

Djahi was the Egyptian name for the land later called Canaan.

Canaan is from a word used for “dealers in purple.”

It came to be used for the northern coastal lands of Djahi.

Much later the Egyptians began to use “Canaan” for all their Djahi territory.

Although the indigenous population of Djahi originally was Semitic,

Hurrians had entered the land centuries earlier, and populated it.

The inland cities now had Hurrian fortifications,

By 1700 BC, all Djahi was infiltrated and well settled by the Hurrians.

In 1620 BC, in northern Djahi, Alalakh was attacked by Hattusili.

Under its king, Hattusili, Hittite borders grew rapidly.

If a city surrendered, it got one of his sons as its ruler.

If a city resisted, Hattusili would raze it to the ground

“When Mursili, Hattasuli’s successor, was king, his sons and troops were united.

He defeated his enemies with a strong arm [and ruthlessness].

He made the sea the boundaries of his land.

He even took Aleppo, in Djahi, which Hattasuli could not do.

Mursili brought resettlers from Aleppo to Hattusa, the capital.

He went to Babylon and destroyed that city in 1595 BC.

[We have no record, but he certainly would have put a “son” there.]

He also fought the Hurrians” in southern Djahi, taking Hazor.

Evidence of Hittite control of Hazor is found in the early basalt work.

It is a very hard rock, which cannot be worked with bronze tools.

Abrasives may do the job, but iron tools are more likely.

At this time, only the Hittite nobility had iron tools.

The destruction of Jericho has also been incomprehensible to historians,

Yet it can be reasonably be attributed to the Hittites, under Mursili.

Who else was as active as Mursili at that time? “No-one” is the answer.

Poor Jericho! Its great fortifications could not save it from destruction.

When Mursili returned to Hattusa, the capital, he was killed in a palace coup.

Mursili was killed by his brother-in-law, Hantili, and Hantili’s son-in-law.

Seizing the moment, the Hurrians struck out, reaching as far as Hattusa.

The Hittite rulers did not understand that their ruthlessness had a cost.

What were Mursili’s “sons” now to do? The evidence is clear.

The new outposts of empire were lost. Babylon was taken by the Kassites.

The Hittite ruler of Hazor was free of the king at Hattusa.

Disgusted with his “father’s” murder, he owed no allegiance to Hantili.

By 1545 BC, the Egyptians had expelled their foreign rulers, the Hyksos.

Weakened by the Hittite incursions, the Hyksos were left friendless.

Pharaoh Ahmose defeated the Hyksos, who were originally from Djahi.

No help came to them from the dynasty of Yamhad, based on Aleppo.

Pharaoh Ahmose established a new Egyptian dynasty, the 18th dynasty.

The chief god of Thebes, Amun, became the highest god of the land.

With “Amun’s help,” Ahmose took the Hyksos fortress of Sarunhen, near Gaza.

He also ventured further into Djahi, but did not create much of a legacy there.

Around 1530 BC, Abram and Lot arrived in Djahi.

They soon each had so many sheep that they had to separate.

Lot went to live among the Canaanites on the coast.

Abram continued to live inland, in Hittite territory.

While the intrepid adventurers were building their pastoral enterprises,

Pharaoh Thutmoses III was creating a new Egyptian empire.

From 1479 BC, in repeated campaigns, he crushed all opposition.

He established outposts in Djahi and demanded annual tribute payments.

When Thutmoses died, the king of Kadesh on the Orontes rebelled.

Every city from that region joined in; Hazor made a minor contribution.

Yet Pharaoh Amenhotep II defeated them all in battle.

Shut up in Mediggo, after six months they all submitted to Amenhotep.

After living for ten years in Djahi, Sarai gave her maid to Abram.

She said to him, “Take Hagar, my maid, as your wife.”

So Abram took Hagar as his second wife, and Hagar became pregnant.

When the time arrived, Hagar, the Egyptian, gave birth to his son Ishmael.

After this, Sarai also become pregnant to Abram.

When the time arrived, Sarai, his first wife, gave birth to a son.

He called this son, Isaac. He was a son born to him in his “old age.”

Isaac was my grandfather, and Ishmael was my grandfather’s brother.

Abram, Sarai, and his two sons lived near Kiriath Arba, a Hittite city.

Kiriath Arba was a town with Hurrian fortifications, a “kiriath.”

It was a dependency of Hazor, the pre-eminent Hittite city of Djahi,

While Hazor was a city-state in Djahi, it remained a loyal Egyptian vassal state.

Sarai died near Kiriath Arba. She had lived a rich life and was full of years.

Abram grieved for Sarai and wept for her: he loved her very much.

Wanting a place to bury her, he went to Hittite leaders in Kiriath Arba.

He said to them, “I am an alien amongst you. Grant me a place to bury my wife.”

The Hittite leaders said to Abram, “You are a chieftain among us.

Bury your dead in the choice of our tombs.”

Abram said to them, “Please intercede for me with Ephron, son of Zohar;

Ask him to sell me the cave of Machpelah, on the edge of his field.”

Ephron was sitting there. He said to Abram, “I will give you the field!”

Abram replied, “I must pay for the field. What will it cost?”

Ephron replied, “The land is worth 400 shekels of silver.”

Abram weighed out the silver to Ephron, and he bought the field and cave.

Abram buried Sarai, his wife, in the cave of the field of Machpelah.

The field is located near Mamre in the land of Djahi.

It became Abram’s property and remained as a lasting inheritance.

The deed was established and witnessed before the Hittite leaders of the town.

Hittite law governed the transaction for the purchase of the field and the cave.

The Bible account is saturated with the subtleties of Hittite law.

It tells us that, along with purchasing the field, the cave and its trees,

Thus Abram also acquired a formal relationship with the king of that place.

Many have tried to defend the idea of the “verbal inspiration” of the Bible.

Some have even argued the Israelites entered Egypt during the Hyksos period.

This proposition, relying on one verse, composed much later, is foolish.

Why try to place the Hittites in Djahi before they even entered that region?

Abram lived to a good old age; he lived a full life.

Finally he died and was gathered to his people.

Isaac and Ishmael, his sons, buried him in the cave of Machpelah,

Which Abram had bought from the Hittites, and where Sarai was buried.

Ishmael also lived a good long life, who knows how long?

Twelve chieftains and twelve tribes came from his loins.

The first was Nebaioth, followed by Kedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, Mishma, Dumah, Massa, Hadar, Temar, Jetur, Napish and Kedmah.

They dwelt from Havilah, by Shur, all the way to Assyria.

Joseph died during Amenhotep III’s lifetime (d. 1323 BC).

Joseph indicates that Ishmaelite territory in his time went up to Assyria.

This make sense: at that time, Assyria territory went down to the Red Sea.

This points to this story being both contemporary and historical.

When Esau was forty years old, he took a wife.

He first married Judith, the daughter of Beeri, the Hittite,

Then he married Basemath, daughter of Elon, the Hittite.

These two women brought bitterness to the spirit of Isaac and Rebekah.

Rebekah said to Isaac, “I am disgusted with my life because of Esau’s wives.

If Jacob also takes a wife like these women, I will be very unhappy.”

So Isaac said to Jacob, “You shall not take a wife from the women of Djahi.

Go to Paddan Aram, to your mother’s father, and take a wife there!”

So Jacob, having listened to his father and his mother, went to Paddan Aram.

There he married Leah and Rachel, Laban’s daughters.

After Isaac left, Esau saw that his marriages had displeased Isaac and Rebekah.

So he also took a new wife, a cousin, Mahalath, the daughter of Ishmael.

Leah gave Jacob sons: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar and Zebulun.

Benjamin is a son of Rachel, and so am I!

Rachel’s maid, Bilhah, gave birth to Dan and Naphtali.

Leah’s maid, Zilpah, gave birth to Gad and Asher.

With his wives and children, Jacob returned to his father near Kiriath Arba.

Isaac died there. He was gathered to his people, old and full of days.

Esau and Jacob, his sons, buried him in the family tomb, as was required.

The two brothers were now free to separate: they had fulfilled their duties.

It was clear that their vast herds were too much for them to live together.

So Esau took his wives, sons, daughters and servants and went to Mount Seir.

But Jacob continued to live in the land of his father’s sojourn, in Djahi.

Esau went away from Jacob, my father. Esau became the ruler of Edom.

From Djahi, I found my way to Egypt, serving one of Pharaoh’s servants.

In 1397 BC, when I was thirty years of age, I stood before Pharaoh.

Then I invited my whole family to come to Egypt with all their property.

Seventy persons came: Jacob, his sons, grandsons, daughters and granddaughters.

Pharaoh Thutmoses IV said to me, “Your father and brothers have come.

The land of Egypt is before you; settle them in the best of the land.

They can live in the land of Goshen, where they can feed their flocks.

If there are worthy men among them, they can manage my flocks.”

So I brought my father to be introduced to Thutmoses.

Pharaoh said to Jacob, “how many years have you lived?

Jacob responded, “One hundred and thirty years.

My days have been few and bad, not like my fathers’ long lives.”

While the Egyptians could calculate the years of their lives,

Such as those living in non-literate social groups, as Abram’s family,

Could only guess their ages. Jacob clearly assumed that older is better.

This then shaped the ages given to all the patriarchs in the Priestly Source.

After this, I settled my father and brothers in Goshen.

They gained a place in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land.

They lived there, just as Pharaoh had commanded,

And I supplied them all bread according to their numbers.